Sophie Rowley’s exploration into the materiality, sustainability, and spirit of design

Reclaiming the Future

-

Designer Sophie Rowley

All images courtesy of the designer

-

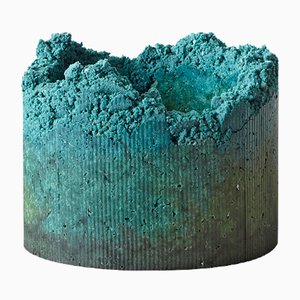

Rowley's Perna Viridian Disc made from discarded CDs

-

Rowley worked with local craftsmen in India during a recent one year stay

-

Material explorations

-

Material explorations

-

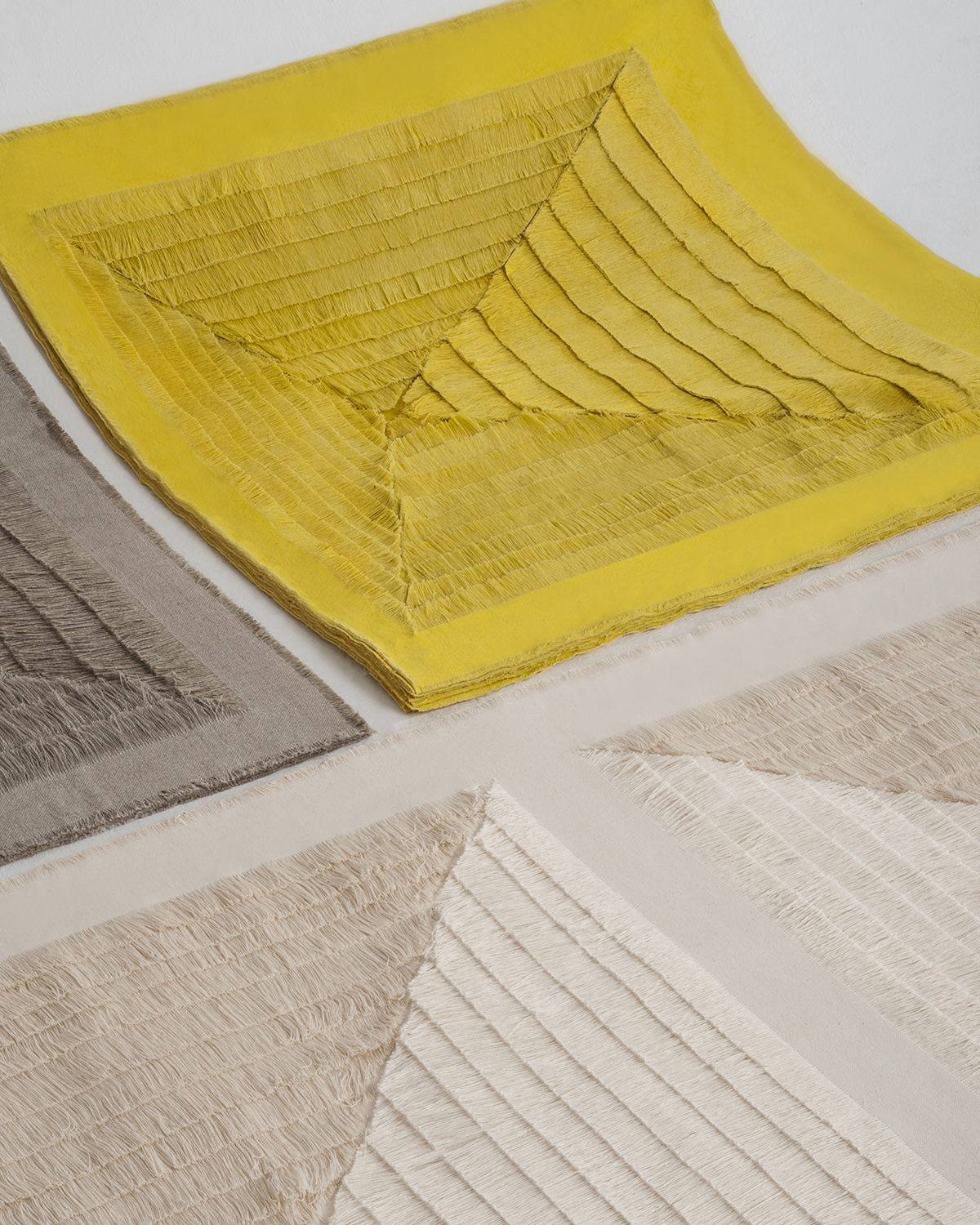

Rowley's Khadi Frays series, hand-dyed cotton using Indian Tumeric

-

Rowley's Khadi Frays series of textiles developed during a recent one-year stay in India

-

Rowley's Khadi Frays series of textiles developed during a recent one-year stay in India

-

Facing wood waste

-

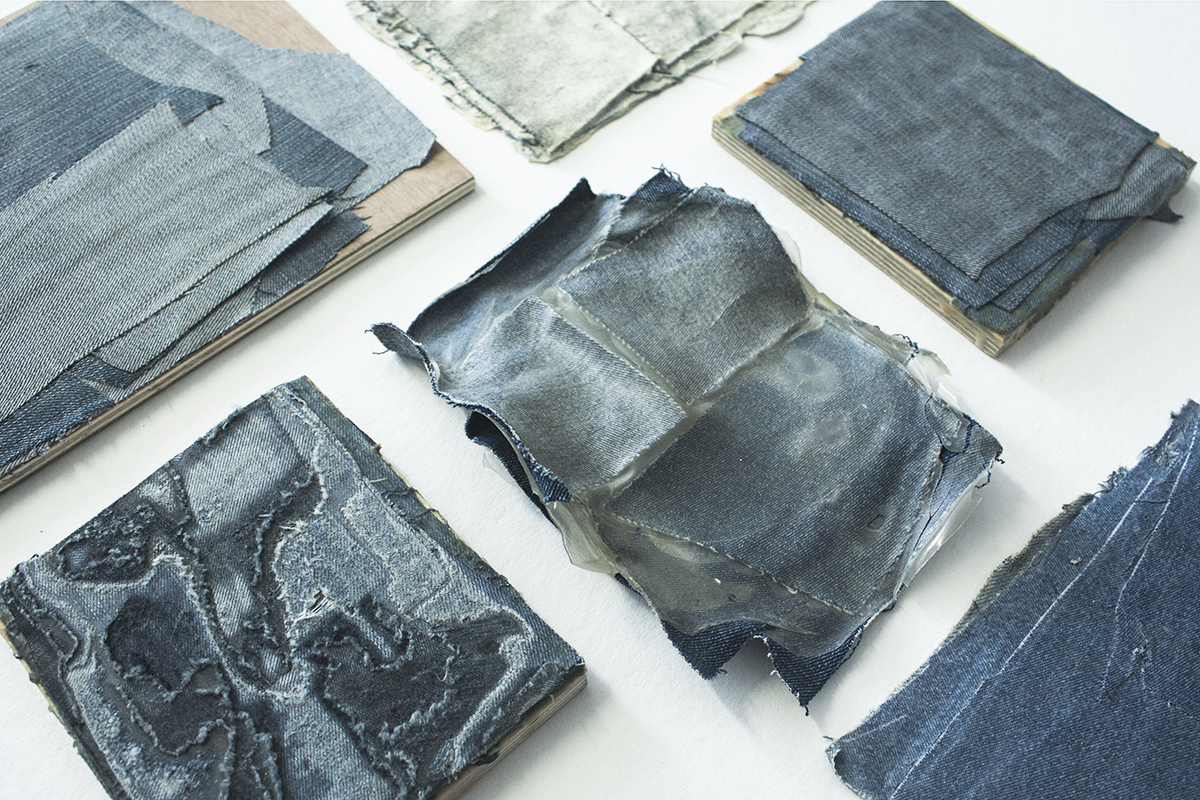

A look into the process for Bahia Denim

-

Blue Foam and Perito Moreno Glass

-

Recycled green glass

-

Kaibab Bowls made from offcuts of sheet foam sourced from a London-based mattress vendor

Berlin-based designer Sophie Rowley has been on Pamono’s design radar for a few years now. As editors and curators, we love celebrating creatives who use their skills to help make the world a better place. Rowley’s work is focused on turning trash into treasure, transforming industrial waste into spectacularly intricate materials that mimic natural forms and textures. Her Perito Moreno Platters, for example, are made from reclaimed glass; her Silverwood Door Weight from reclaimed newspapers; her Kaibab Bowls from reclaimed mattress foam and paint; and her Bahia Stools from post-consumer jeans waste. We went to Rowley's studio to learn more about her brilliant, alchemical approach.

Set inside an old industrial paper factory in Neukölln, a rough-around-the-edges district populated by hipsters, vintage cafes, and cool bars, Rowley’s studio is petite and spare. One wall is occupied by a make-shift kitchen and a shelf exhibiting her material experiments—modestly presented yet strikingly beautiful in its spartan setting. A corner is filled with scrolls of paper and stacks of her Bahia Denim slabs; another, drenched with sunlight from the window, holds a broken wooden chair frame that she is in the process of refurbishing.

Rowley has just returned from a short stay in Japan where her Khadi Frays Woven Textiles were chosen as a finalist for the 2019 Loewe Craft Prize and exhibited at Isamu Noguchi’s indoor stone garden, Heaven, in Tokyo. She's loved to travel and immerse herself in different cultures ever since she was a child growing up between New Zealand's North Island and Southern Germany. After stints in various corners of the world, she moved to Berlin to study Textile Design and then to London for her MA in Material Futures from Central Saint Martins.

It was in London that Rowley first became serious about working with waste materials, even though she'd dabbled with it for years. “I guess it was always something I did but didn't really notice at first," she says. "Even when I studied textiles in Berlin, I often used found materials for my projects.” And while traveling and sustainability have inspired her work immensely, she confesses that choosing to work with found materials and offcuts began with a rather humble motivation: money. “As a student, I didn’t have a lot to spend on materials," she explains. "So I went around to various factories and collected their material waste.” It was a happy accident to be sure, because by now Rowley has a mini-library of new materials that she's invented from scraps.

Bahia Denim so far has garnered the most attention from international tastemakers. To make it, she layers the denim offcuts into molds and presses them into shape with the help of bioresin. Once dried, she hand carves each piece, ensuring a smooth surface that's reminiscent of the Brazilian blue marble it's named after. The different washes of the jeans appear like the veins in marble, lending incredible depth to the material.

Her more recent Khadi Frays project emerged from time spent in India, where she collaborated with like-minded designers and artisans to apply traditional Indian craft techniques to waste material. Rowley started experimenting during her free time with Khadi—hand-spun, hand-woven fabrics that have a very specific importance in India, inspired by Gandhi’s notion of the Khadi Spirit, the state of limitless patience in the fight for freedom. During colonial times, the vast majority of the cotton fiber that was produced in India was sent to Great Britain. Khadi was a "protest" fabric produced in India for Indians; a means for Indians to support their own economy and become independent from Great Britain.

Rowley's Khadi Frays pays homage to the Khadi Spirit and India’s heritage, celebrating the intense labor involved in creating the Khadi material. Rowley reverses the process by layering each piece of fabric and undoing each of the 10,000 threads—patiently, one-by-one, in an almost ritualistic manner—leaving a frayed, geometric frame. The differences in the warp and weft allow the layers to reveal variations in tensions, colors, and textures. The end result is as complex, rich, and layered as the country itself.

“The Khadi Spirit is represented in the process of making the fabric as it is very manual,” Rowley explains as she shows me examples of her work, one of which is dyed a cheerful yellow using tumeric. Laughing, she continues: “I had a yellow bathtub for months after this one. Dying the fabrics myself is really nice, because I can control the outcome more easily. But the work is incredibly physical.”

Rowley has not chosen the easiest path, particularly given the inconsistencies inherent in waste materials. Case in point, different viscosities and different chemical components in paint waste impede her from pursuing the path of that material further. Each new product must be tested through trial and error several times over, and all that R&D can get costly. But Rowley’s hard work into creating new materials is getting noticed. Currently, Ph.D. students at Berlin’s Technical University are testing the tensile strength of Rowley’s Heliopora Foam to determine its viability for large scale production.

“We are at a point in history when can no longer create," Rowley says. "Rather we must recreate using materials that have already been produced; that have had already a life. This is our challenge." Rowley is up for it. In October, she plans to travel back to Mumbai to work in collaboration with Studio Raw Materials. They have received funding to work with a common natural material found in India. Rowley isn't sure yet what they will (re)make, but we're sure it'll be magic.

-

Text by

-

Rachel Miller

Rachel is a California native whose passion for travel has led her on some pretty crazy adventures around the world. After living in Korea for three years, she decided on a whim to move to Germany. While she still has a wandering soul, Berlin has captured her heart, and she's decided to make this multicultural hub her permanent home. Most of her free time is spent playing beach volleyball, exploring the city's many arty scenes, and hunting down Berlin's best craft beer.

-

More to Love

Industrial Craft Table 02 by Charlotte Kidger

Shikkui Hemp Table Stand by Yasmin Bawa, 2019

Industrial Craft Vessel 02 by Charlotte Kidger

Industrial Craft Table 03 by Charlotte Kidger

Black & Beige Cotton Bowl by Krupka-Stieghan

Small Well Proven Stool by Marjan van Aubel & James Shaw for Transnatural Label

Medium Well Proven Stool by Marjan van Aubel & James Shaw for Transnatural Label

Large Well Proven Stool by Marjan van Aubel & James Shaw for Transnatural Label

LAAB-Light & Leaves Pendant Lamp (Model L) by MIYUCA

Structural Skin Table Lamp Nº02 by Jorge Penadés, 2017

Structural Skin Table Lamp Nº03 by Jorge Penadés, 2017

Reaching various binders for her Bahia Denim material

Reaching various binders for her Bahia Denim material

Khadi Frays textiles made from natural cottons hand-dyed in Indian tumeric

Khadi Frays textiles made from natural cottons hand-dyed in Indian tumeric

Rowley's Khadi Frays series of textiles developed during a recent one-year stay in India

Rowley's Khadi Frays series of textiles developed during a recent one-year stay in India