The rise and fall and rise of Piero Fornasetti

Fornasetti Revealed

-

Wall Clock in Glass by Fornasetti, Italy, 1990s

Photo © Maden di Marta Leo

-

Vintage Decorative Gift Object by Fornasetti, 1950s

Photo © IMPORTANT DESIGN di Herat De Nicola

-

Decorative Porcelain Plates by P. Fornasetti for Martini & Rossi, 1960s, Set of 12

Photo © BorFor Vintage S.R.L.

-

Mid-Century Modern Fornasetti Coffee Table, 1950s

Photo © Love Italian Antiques

-

etal Janus Two-Faced Bookend by Pietro Fornasetti, 1950s

Photo © Bologna Design Gallery

-

Small Coasters in Porcelain attributed to Piero Fornasetti, Italy, 1950s

Photo © iMadons Design

-

Photo ©

-

Basket by Piero Fornasetti for Atelier Fornasetti, 1950s

Photo © Antichità Brighenti Fausto

-

Sun Floor Lamp by Piero Fornasetti for Antonangeli, 1990s

Photo © Maden di Marta Leo

-

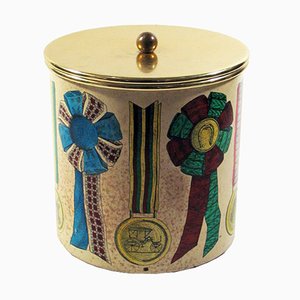

Box by Piero Fornasetti, Italy, 1970s

Photo © Maden di Marta Leo

-

Musicale Chair by Piero Fornasetti, 1950s

Photo © Symple Design

-

Mid-Century Tripod Coffee Table Butterflies from Piero Fornasetti, Italy, 1960s

Photo © Aenigma Design Gallery di Giovanni Taddeucci

-

Louis XV Style Chests, 1950s, Set of 2

Photo © Gustavian - EU

-

20th Century Trinket Box by Piero Fornasetti, Italy, 1970s

Photo © Pushkin Antiques

Piero Fornasetti was a true original in the landscape of mid-20th-century design. Unlike many of his modernist contemporaries, he focused on surface enrichment rather than form, covering the surfaces of furniture, tableware, and textiles—even entire rooms—with his witty and surreal hand-painted images. Because his work is decorative in nature, his name is often missing or presented as a side-note in studies of classic Italian design. Yet the extraordinary range of items he produced through his atelier, numbering over 11,000, testifies to both his popularity and to his limitless imagination.

From the very beginning of his career as an artist, Fornasetti went against the grain. He was expelled for insubordination from the Academia di Belle Arti di Brera in 1932, two years after entering. Undaunted, he participated the following year in a student exhibition at the University in Milan, and then he showed a series of printed scarves at the fifth Triennale in Milan. Early on, he experimented with architectural decoration, such as frescos in public spaces and the decorative bronze and ceramic frieze created for the sixth Triennale in 1936.

Fornasetti might not have found popular success without the help of the powerhouse designer Gio Ponti. In 1940, the two began a collaboration that would yield some of Fornasetti’s most beloved works. Ponti was attracted to Fornasetti’s neoclassicist motifs and references to the Italian visual heritage. In turn, Ponti offered Fornasetti expansive surfaces on elegantly proportioned furniture, a solid base on which to try out with all manner of graphic patterns and spatial illusions. Secretaries were decorated with illusionistic bookshelves; doors overlaid with fictional invitations; a radiogram papered in sheet music.

The Architettura series is perhaps the most successful collaboration of the duo. Debuting at the 1951 Triennale, this collection exemplifies the full expression of Fornasetti’s style. Based on antique architectural prints, the imagery consists mainly of neoclassical building façades and interiors, which envelope Ponti’s furniture and play with perceptions of volume and surface. The illustrated architectural elements were positioned in dialogue with the furniture pieces: trompe l’oeil staircases lead to real surfaces and real interior spaces, whilst the real interior of a cabinet is transformed by trompe l’oeil interior architecture.

This interplay between two and three dimensions became an integral part of Fornasetti’s designs. He drew from a vast array of printed sources, including maps, advertisements, typography, and illustration, ranging in date from the 17th to the 20th centuries. He celebrated the historical nature of these images, often painstakingly reproducing the engraving marks. The Tema e Variazioni series, based on a 19th-century magazine illustration of the opera singer Lina Cavalieri, consists of hundreds of images of this woman’s face. Though the face has been blown up, shifted around, and endlessly reworked with Fornasetti’s signature tongue-in-cheek humor, the engraver’s crosshatchings remain integral to the image, tying it firmly to its origins as an historic image.

As his collaboration with Ponti tapered off, Fornasetti’s output grew in quantity and scope, producing an array of new products including trays, posters, vests, lamps, bicycles, screens, plates, ashtrays, umbrellas, and lamps, as well as large-scale projects such as set designs for La Scala, interiors for the casino at Sanremo, and interior elements for the ocean liner Andrea Doria. He often revisited images in endless permutations: in addition to architectural elements and Lina Cavalieri’s face, he experimented with suns, butterflies, fish, playing cards, and hot air balloons, among many other motifs. Sometimes the decorations floated across the surface completely autonomously, at other times they playfully interpenetrate the material forms.

By the end of the 1960s, Fornasetti’s work was diminishing in popularity, overshadowed by more avant-garde and conceptually-driven design work, epitomized by Museum of Modern Art’s 1972 landmark exhibition, Italy: The New Domestic Landscape. Apparently only a few somber stripes or checks were allowed in this new, futuristic landscape. Fornasetti’s fortunes declined, and his workshop in Milan slowly dwindled from 30 workers at its peak in the 1950s to only 3 employees.

In the 1980s, however, the emergence of Postmodernism brought with it a renewed interest in surface decoration, and by the time of Fornasetti’s death in 1988, his work was once again attracting attention. In 1991, the Victoria & Albert Museum in London held a major retrospective, and since then, the prices of Fornasetti objects have been steadily rising on the primary and secondary markets. Fornasetti’s son, Barnaba, who began to reestablish the company in the 1980s at his father’s request, has reissued many of the older designs and introduced new lines, in keeping with his father’s vision.

In the end, Fornasetti’s interest in the past was indicative of the future. His interest in imaginatively decorated surfaces and witty historical quotations presaged postmodernism. His work has endured as unique and distinctive, and he ensured his legacy by remaining committed to his vision, even in the face of modernist austerity and the vagaries of fashion. He summed up his philosophy in an interview in 1987, just before his death: “An artist who wants to be successful is no longer an artist. If he conforms to fashion, he will arrive late because by now everyone has already conformed. Therefore, perhaps, the idea is not to conform but to be original.”

-

Text by

-

Jennifer Scanlan

Jennifer is an independent curator, writer, and teacher specializing in contemporary art and design. She loves food, travel, and her home city of New York. You can also follow her on Twitter @JenScanNYC

-

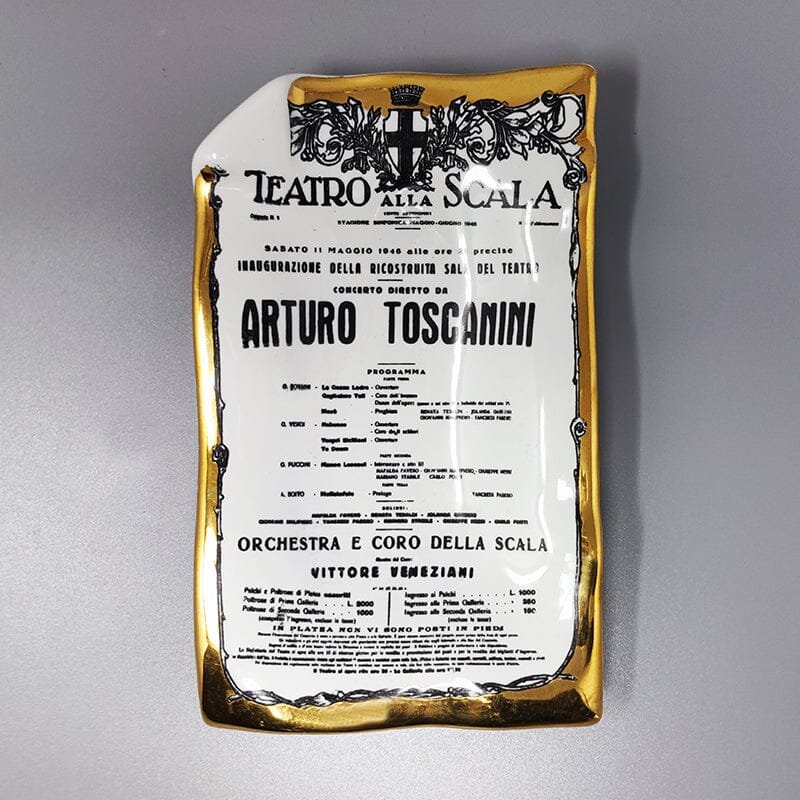

Arturo Toscanini Porcelain Catch-all by Piero Fornasetti, Italy, 1960s

Photo © Maden di Marta Leo

Arturo Toscanini Porcelain Catch-all by Piero Fornasetti, Italy, 1960s

Photo © Maden di Marta Leo